Grapes Of Wrath

Pashtun children huddle around bonfire after collecting trash

Irfan Ali Turi says that he is often mistaken for being Balti or Hazara due to his East Asian features. Irfan Ali completed his secondary education from Kurram Agency. He got his BBA (Hons) degree from the Institute of Business Management Studies (IBMS) at the Agricultural University, Peshawar. His time at college was divided between his hostel and being trapped in his village due to continuous war in Kurram. After completing his degree in such circumstances, he moved to Rawalpindi as many students from Kurram were either kidnapped or killed in Peshawar. In Islamabad he started working for Pak-Motor Traders for few months. He then left that job for another opportunity at a steel mill in Tanzania.

Rehmat Ullah serves tea

Rehmat Ullah and his family fled Karachi’s ethnic strife

He spent one year there and came after having developed severe issues with the management. Irfan helps his family in farming when he is at his village. He is also a good cricket player. He is a well-known player in Kurram and he is approached by different teams when cricket tournaments take place in Parachinar. He is unemployed just like thousands of other young men. Most students from Kurram migrated legally or illegally to Australia or Europe. He also applied for an Australian visa last year but it was rejected. According to the consultant he engaged, the Australian embassy is rejecting student visas for Pashtuns, since many Pashtuns apply for asylum soon after arriving in Australia. He lives between Rawalpindi and Kurram. Many of his friends have migrated. Villages are deserted now, and he understands that his working on the farm can’t change the fate of his family. So he moves between Kurram and Rawalpindi. Young men in his village complain about Irfan’s attitude. He can get into fights even when playing cricket or football. To this, Irfan replies that it is the only space where he can relieve his anger.

The future is bleak for children displaced by war in Pakistan and Afghanistan

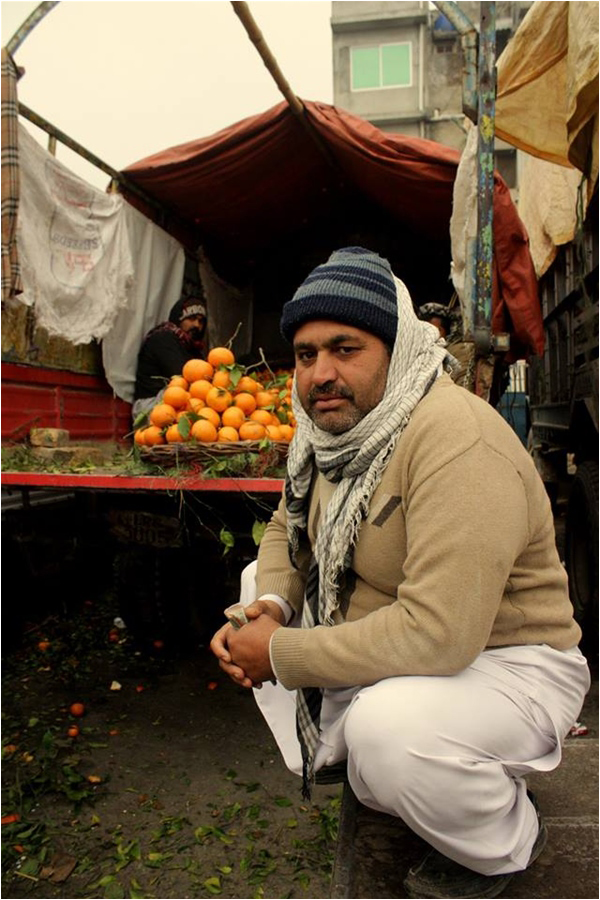

Noor Mohammed used to live in the now demolished I-11 katchi abadi settlement. He works at Islamabad’s Sabzi Mandi (vegetable market). According to him, his family came to Islamabad when he was 15 and settled in the I-11 squatter settlement. As is common among Pashtun families there, they move between Mohmand and Islamabad. Noor Mohammed is very active politically since his early days. He was always involved in community development activities in I-11 and in the Mohmand Agency. He is now an active member of the Awami Workers’ Party, Islamabad. During last year’s local body elections, he ran for a seat from the AWP’s platform. Just like thousands of slum dwellers, his house was razed by the Capital Development Authority (CDA) last year in July. He mobilised his community and campaigned for their houses to be spared. Due to his political activism, he has been nominated in many police reports. He couldn’t go back to Mohmand Agency due to the poor law-and-order situation and also because his only source of income is the Sabzi Mandi in Islamabad. He says that before launching its operation to clear the I-11 settlement, the CDA conducted ‘propaganda’ against them, insinuating that the residents were “Afghans, criminals and terrorists”. He says police harassment is a daily experience for him.

Rehmat Ullah’s Quetta cafe

Rehmat Ullah Achakzai comes from Qila Abdullah, Balochistan. He, along with his family, runs a chain of ‘Quetta Cafes’ in Rawalpindi and Islamabad. Many Pashtuns from Balochistan move to Karachi in search of employment. Rehmat Ullah used to run a Quetta Café in Karachi. When Karachi was burning during an ethnic war, the chief targets of violence were often people from ‘humble’ or working-class backgrounds. Rehmat Ullah and his family decided to move to Rawalpindi-Islamabad. At his Quetta Café in Rawalpindi, he has posted signs stating, “Please avoid political discussions”. Known for its special chai and popular among students, Rehmat’s Quetta Café is a bustling spot in the Commercial Market, Rawalpindi. As for Rehmat Ullah, all he wants is a peaceful life, secure in the knowledge that he and his loved ones can’t be gunned down the next day.

Noor Mohammed

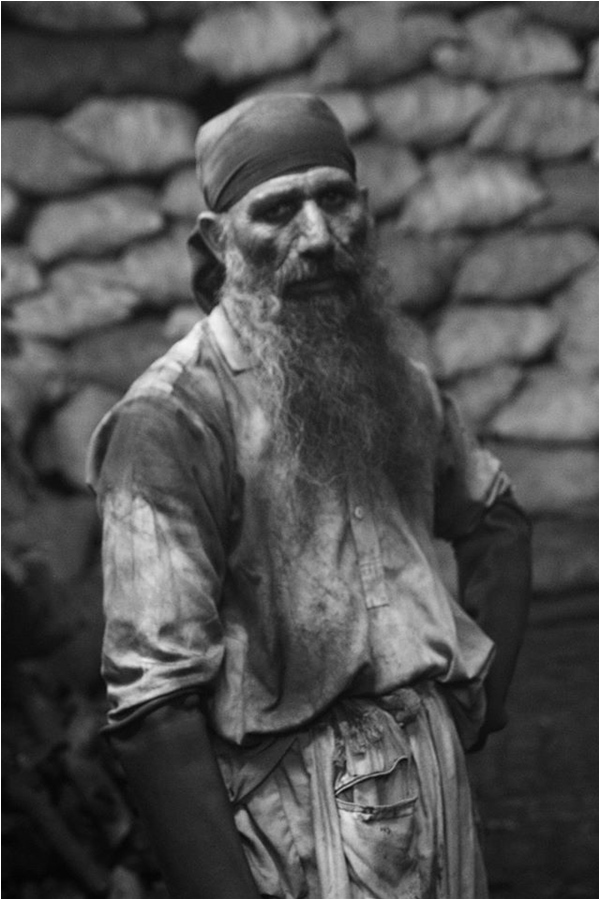

Zarbat Gul says that he is seen with suspicion by people because of his Pashtun identity and his facial hair

A number of children are warming themselves at a bonfire after collecting trash. Kaleem Ullah, Noor Wali and Rahim Gul hail from Jalalabad in Afghanistan, while Zalmay is from Waziristan in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan. The families of the Afghan children immigrated to Pakistan after the entry of Soviet forces and since then they have visited Afghanistan once or twice in their life. In Pakistan, Afghans are often equated with ‘terrorists’ and blamed for the religious and sectarian violence that is tearing apart Pakistani society. After the tragic terrorist attack on the Army Public School (APS) in Peshawar, thousands of registered and unregistered Afghans were expelled from Pakistan. They are daily harassed by police, stereotyped and ostracised by ordinary Pakistanis. During all this, Pakistanis forget who was training and arming fundamentalists. These children face the choice between a devastated home country (Afghanistan) and an increasingly hostile adopted country (Pakistan). These children are resilient in facing everyday hatred and intimidation. One wishes their resilience had been tapped for better reasons, such as studies.

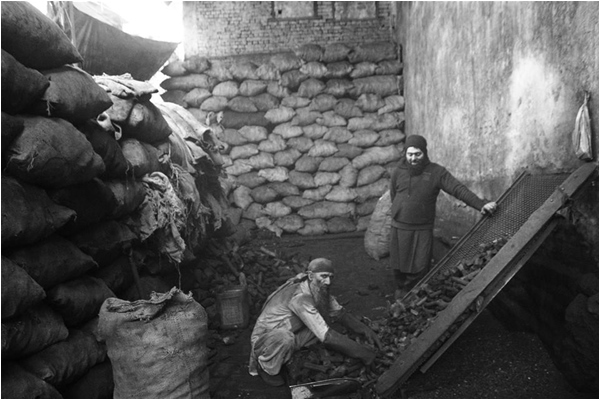

Zarbat Gul at Work

Zarbat Gul

Zarbat Gul Kaka hails from Mohmand Agency (FATA), working at a coal factory in Bhor Bazar, Rawalpindi. FATA is one of the least developed regions in Pakistan. Ignored for years, still governed by colonial law under the Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR), its residents rely on agriculture and remittances from relatives in foreign countries for their income. Due to unavailability of employment opportunities and continuous wars many people have left FATA for big cities. Zarbat Gul Kaka is one of them. He works for twelve hours to feed his family in Mohmand Agency. He has decreased his frequent visits to his village when the security situation worsenend in Mohmand – facing the suspicion of authorities and violence by the Taliban. Zarbat says that he is seen with suspicion by people because of his Pashtun identity and his facial hair. “We are tired of explaining and clearing ourselves!” he exclaims.